LLM Word of the Week : Embeddings

The hidden “map” that lets a language model understand what words look like inside its brain.

Before “Embeddings”: How we used to tell a model about words

The earliest NLP models spoke a very blunt language.

Each word was turned into a one‑hot vector—a list of zeros with a single 1 in the slot that belongs to that word.

v(“cat”) = [0, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, …] ← “cat” is the 4th word in the vocab

v(“dog”) = [0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0, …] ← “dog” is the 5th wordWhat’s the problem?

| Issue | Why it hurts the model |

|---|---|

| Huge, sparse vectors | Millions of words → millions of dimensions → slow math and huge memory. |

| No sense of similarity | “cat” and “dog” are as far apart as “cat” and “quantum” – the model can’t guess they’re related. |

| No handling of new words | A word not in the list gets no vector at all. |

So the model could read a sequence of numbers, but it had no idea which numbers meant “similar ideas”.

What an Embedding really is (in plain language)

Embedding = a learned, short list of numbers that describes a word (or token) in a way that similar words end up close together.

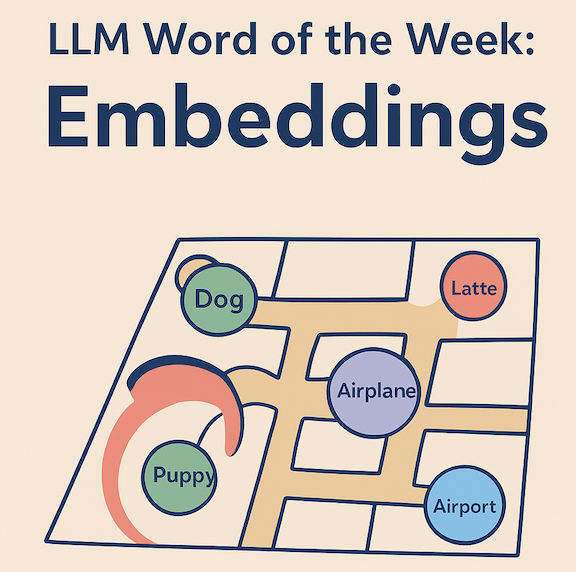

Think of a vector as an address on a map:

- In a city, you can describe a location with just a few numbers (e.g., latitude = 37.77, longitude = ‑122.42).

- In an embedding space, each word gets its own “latitude/longitude” (actually dozens or hundreds of coordinates), and the distance between two points tells you how similar the words are.

Tiny numeric example (2‑dimensional for illustration)

| Word | Vector (x, y) |

|---|---|

| cat | (0.7, 0.9) |

| dog | (0.6, 0.85) |

| kitten | (0.71, 0.88) |

| car | (‑0.2, 0.1) |

| quantum | (‑0.9, ‑0.4) |

- Euclidean distance (think “straight‑line” distance) between cat and dog ≈ 0.11 → they’re near each other.

- Distance between cat and quantum ≈ 1.82 → they’re far apart.

The model learns these coordinates by looking at word co‑occurrence: words that appear in similar contexts end up with similar coordinates.

The breakthrough moment

| Year | Paper / Technique | Core Idea |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | Word2Vec (Mikolov et al.) | Skip‑gram & CBOW learn dense vectors by predicting neighboring words. |

| 2014 | GloVe (Pennington et al.) | Factorizes a global co‑occurrence matrix → similar quality, different math. |

| 2018 | ELMo (Peters et al.) | Contextual embeddings: the same word gets a different vector depending on its sentence. |

| 2019‑present | BERT, GPT, T5, … | Embeddings become the input layer of massive Transformers; plus position embeddings that tell where each token sits in a sequence. |

These works showed that you could compress meaning into a handful of numbers and that the geometry of those numbers captures syntax, semantics, even analogies. That discovery is the foundation of every modern LLM.

Why embeddings matter to you (and to every AI product)

| Use case | How embeddings power it |

|---|---|

| Semantic search | A query “cheap laptop with good battery” is turned into a vector; the system retrieves documents whose vectors lie close by. |

| Recommendation engines | Movies, songs, or products are plotted in the same space as users’ past likes → nearest‑neighbour suggestions. |

| Cross‑language understanding | “dog” (English) and “perro” (Spanish) acquire similar coordinates, enabling zero‑shot translation. |

| Few‑shot prompting | Because vectors already capture high‑level concepts, a model can generalize from just a couple of examples. |

| Bias detection & mitigation | Problematic associations (e.g., gender ↔ profession) appear as directions in the embedding space, making them visible for auditing. |

Whenever an AI says “these two items are similar” or “I found a relevant passage,” it’s comparing embeddings behind the scenes.

Simple analogy – the library map

Imagine a huge library where every book is placed on a floor plan according to its topic:

- One‑hot: You only know the title of each book; you have no idea where it sits on the floor.

- Embedding: Each book has a coordinate (x, y). Books about cooking cluster in one corner, sci‑fi novels in another, and biographies spread elsewhere.

If you walk to the “cooking” corner, you instantly see all the related books—even ones you’ve never heard of—because they’re nearby on the map. That map is the embedding space; the AI uses it to wander swiftly from “cat” to “dog” without getting lost.

Final thought

Before embeddings, language models could only see words as isolated symbols.

With embeddings, they gain a spatial intuition—a mental map where meaning is a location you can measure, compare, and move through.

That map is the silent workhorse behind semantic search, recommendation, translation, and the very understanding that powers today’s LLMs.

Embeddings turned raw text into a geometry that machines can compute, and that geometry is what lets AI feel that two ideas are “close” to each other.

Next time you type a query and the answer feels “just right,” thank the humble embedding vectors quietly steering the model toward the right corner of its internal map.